I wasn’t trying to give the nuns a hard time in parochial school. Honest, I wasn’t. I was actually a shy, quiet kid; a total introvert who was eager to learn, and eager to please. I was the kid who’d come into a room and flutter around the doorway with big eyes, like a lemur in a tree, watching everyone and hoping someone would come up to me and say, “Hello.” I didn’t start trouble, and I actively avoided those who did.

But I was also a very curious kid—Rudyard Kipling’s “Elephant’s Child” had nothing on me for “Satiable Curtiosity”—and on top of that, I was born psychic. I was also born with past-life recall.

It started early. Someone bumped into my legs underwater while I was learning to swim with the group of kids at a tiny beach near my house, and I was instantly inundated with a flood of past-life memories; five instances of lives when I’d been killed by sharks. I could feel it in my body. I could feel the hard bump and the sharp, sideways jerk, I could see the water turn red around me as I flailed and sank, realizing as a second shark hit me that the reason I wasn’t rising in the water as I kicked madly was because I no longer had legs.

This was long before “Jaws” was a thing, by the way. And I lived in land-locked Illinois. No one had ever mentioned sharks to me in my life (snapping turtles, yes; sharks, no), but in that moment I knew what a shark attack felt like. I remembered it. I’d died there.

And yeah, since I was maybe four or five years old, at the time. I freaked out. And I couldn’t understand why the swimming instructor didn’t know what I was talking about. Didn’t this sort of thing happen to everyone?

The flashes of past-life recall became even more confusing as I was taught—or was it, indoctrinated?–into my mother’s religion. Catechism class got a little dicey one day, when, after hearing about heaven and hell and limbo for what seemed like forever, I was so perplexed that I scraped up the nerve to ask, “What about the other lives?” I was, like, six, and the nun gave me a funny look as she said, “What do you mean?” Cringing under the weight of everyone’s stares, I mumbled, “You know—the other lives. The ones in-between. Where do they fit in?”

It really wasn’t until I came upon the word, “reincarnation” in a Dr. Strange comic book that I, myself, knew what I was talking about, but finding that word to define what I could sense was exhiliarating. I ran into class, clutching that comic, absolutely delighted to be able to share my authentic experience of reality with my teacher. But not only was Sister Una unreceptive to my epiphany, she was Not Amused. The comic book got flung into the trash and I spent the next couple of hours kneeling on my hands in a corner.

My early years in parochial school could be rough, because I sometimes spoke about what I could see. I hadn’t yet learned not to ask embarrassing questions, like, “Why does Father Ted wear ladies’ underwear?” After that gem, Sister Una developed a peculiar habit of “accidentally” sprinkling me with holy water. I swear, she’d look at me and pray that someone would bring back the Inquisition.

So sure, I listened to the nuns and the padres when they’d read from the Bible and pass on the intricacies of Catholic dogma, but, unfortunately for them, I also listened to the out-of-body-beings—the Spirits—who would lounge against the wall behind my desk and comment on the class content. It’s pretty common; if you pick up a book that’s held to be sacred by a number of people, or conduct sacred rituals, like the Mass, you often attract a spirit audience. Since I’d been able to see and hear these guys since birth, it came as quite a shock to me when I realized in catechism class that others couldn’t.

Moreover, it did sometimes leave me in a bit of a dilemma. I was being taught that God was real; that the Holy Ghost was real. I could see and hear JC for myself, so I knew that he was real. But the difficulty was that he didn’t always agree with them.

They were telling me that he was my Lord and Savior; that he was “the Way, the Truth, and the Light,” and here he was telling me directly that Heaven was a state of being, and that Hell was a stance of judgment created by people to punish themselves for transgressions that didn’t even exist.

Okay, so he didn’t use those words. He pretty much just said, “Heaven is when you love one another. There is only the Hell you make for yourself by choosing to suffer.” And, “There is no purgatory, unless you want one,” adding, “And if I and the Father are one, then you and the Father are one.”

That last part was a biggie. It’s kept me puzzling over the nature of spiritual reality for decades.

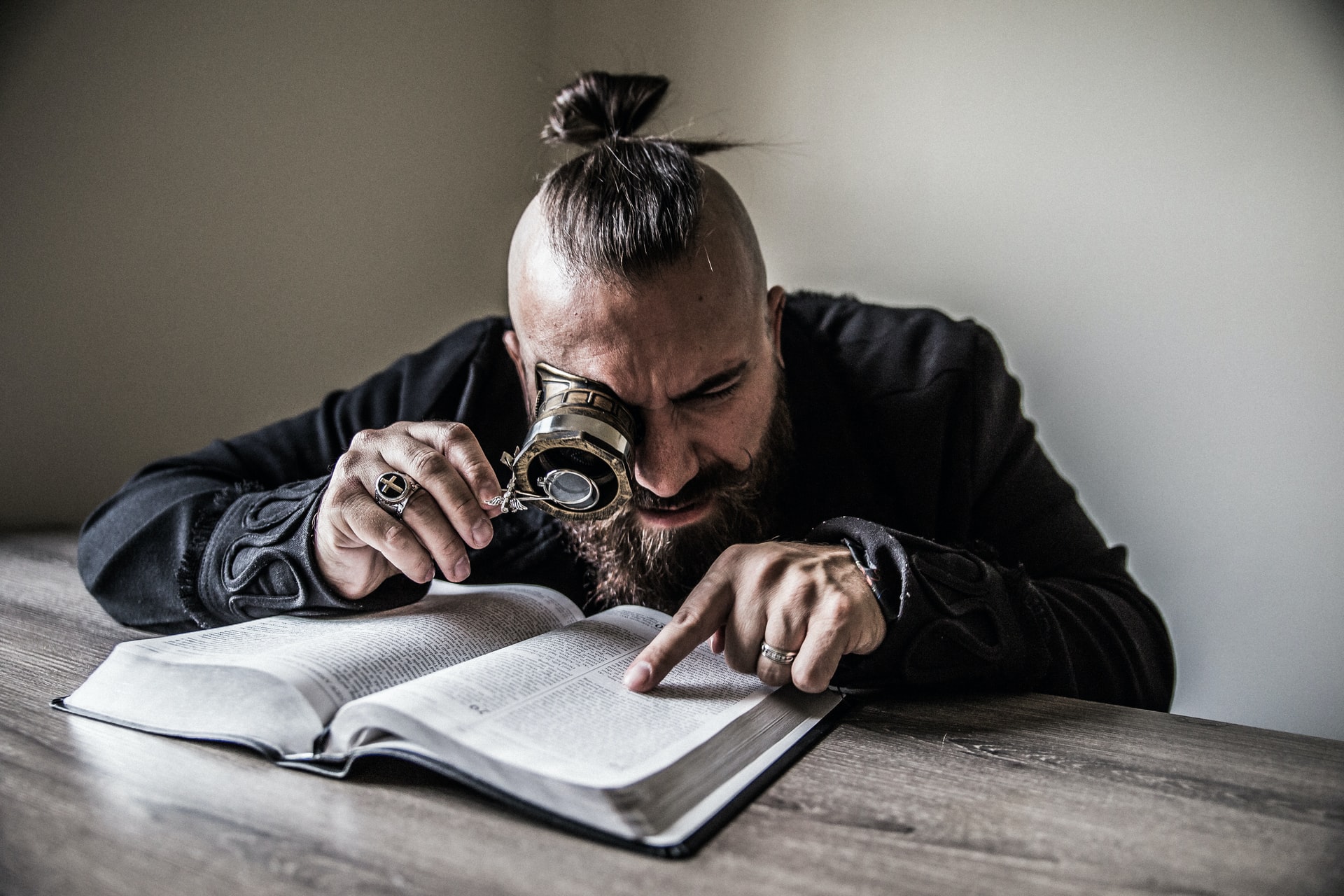

His comments on the Bible were even more casual. Once, after hearing a Bible reading, I’d timidly asked him, “Did you really say that?” and he’d shrugged offhandedly and said something like, “Yeah, kinda, but it meant something different then.” At times, he seemed a tad exasperated by the pedantic nature of the interpretations of Bible passages offered by my religion teachers, seeming to feel that the Bible was just a book—an interesting book, but still, just a book—and like any other book, that everyone who read it should be encouraged to interpret it for themselves. After all, if we’ve each been created in the “image and likeness of God,” certainly we’ve each got the wherewithal to puzzle out the meaning of a few words for ourselves. Or at least give it a shot.

What can I say? The JC I know is big into free will.

Anyway, all of this is a very long-winded way of explaining why I don’t think that the Third Commandment (If it’s slipped your mind, it’s the, “Thou shalt not take the name of the LORD your God in vain.,” one) means that you shouldn’t curse; specifically, that you should never, ever say “God damn it!” It’s certainly polite not to, and does help set your vibration to a place of greater positivity and spiritual respect, or even reverence, but I think it means more than that.

As I see it, the Third Commandment is an instruction to interact with your community in whatever leadership role you choose, but to keep your ego in check, and not be so presumptuous as to assert that you are speaking on God’s behalf. So you don’t say, “God speaks only to ME and you must listen to ME,” to add the stamp of Divine approval to your argument. Dial it back a bit. Say instead, “This is how I see it. This is my take on the matter.”

Do not presume to speak for God. Shun hubris. Speak only for yourself, from your own experience. Period.

Considering how many people have died violently “in the name of God,” each religion or charismatic leader asserting that they are THE voice of the One, True God (when God is obviously completely capable of speaking for him/her/itself), this interpretation makes perfect sense to me. It validates the relationship of each individual to their own, unique view of the Creator, and to the God of their heart. It shows respect for each individual as they determine their own path on their own spiritual journey.

That’s all I wanted to say. The 3rd Commandment, as interpreted by yers trooly, is God saying, “Keep your ego in check, bucko; hands off my name. Show some respect. You’re the creator of your own reality—not your neighbor’s.”